Words of Light

2020 (artist residency projetct in the agricultural high school of La Saussaye in Chartres, France)

Words of Light (after W.H.F. Talbot’s P notebook, 3 drafts about nature and photography) is a project of three fragments created during a three-month residency on the theme of the relationship between Human, Nature, and Culture from October to December 2020, at the Agricultural High School of La Saussaye in Chartres, France.

Initially, the project began with the idea of making Japanese paper using the plants that grow around the school, but it gradually developed, and three different projects emerged. I think this is largely because the isolated environment provided a lot of time to rethink my previous art projects, and the quarantine provided the opportunity to think more than ever about what Time means for us. These three fragments are drafts of a project that is still ongoing in various forms and will eventually be collected into a chapter series exploring the relationship between nature and photography in the early history of photography.

At its origins, and as illustrated by the drawings of animals with black outlines in the Lascaux Caves, Man tried to possess a reality that could only be kept in the form of a substitute. The mimicry of reality, which began with simple outlines, was transformed into a mirror image closer to reality through the invention of various painting techniques. Then, with the introduction of photographic techniques in the early 19th century, mimicry was transformed into a form that could be fixed in less time than a painting and shared with a wider audience.

The pioneers of photographic technique, such as Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot, constantly mentioned the desire to permanently preserve natural phenomena as the reason for their immersion in photographic research and were aware of a close link between photography and nature. This may be explained by the alchemical nature of early photography, which used sunlight as the light source and chemical reactions to fix the image (shadow) by direct contact with the photosensitive material (photogram), leaving the phenomenon to “nature”. In addition to this, Talbot’s photographic research took place at a time when natural philosophy was gradually being replaced by disciplines and forms of investigation that marked the beginnings of modern science, and where our subjectivity, nature and science were inextricably linked. In this context, photography was the new visual evidence for the representation and study of natural phenomena. With the emergence of new disciplines, photography provided new methods of scientific observation and analysis, as well as the need to elucidate abstract principles. This is perhaps the reason why, while explaining scientifically the transformation of nature caused by the camera and chemicals, they took up a vision of natural philosophy, finding “fairy images”, “natural magic” and “words of light” in nature “made visible” by photography.

The invention of the photographic technique also implies the creation of the concept of photography.

Is Nature painted by photography or being induced to paint herself? Is she produced by or a producer of photography? In order to answer these philosophical questions, Niépce, Daguerre and Talbot wondered day and night about the names they would give to the techniques they had discovered, but in the end, no one was able to give a clear answer as to the role played by nature in their photographic art.

Today, when digital images have become the norm, their questions and techniques can be seen as a nostalgia of the past. However, I feel that by revisiting their questions and techniques in our time, we can begin to see some of the chimerical nature of photography. And rather than seeing photography as a means of influencing the emotions of the public, perhaps we need a perspective that categorizes photography in terms of culture and similarity, as well as the imaginations that accompany them?

Production supports :

DRAC Centre-Val de Loire

Conseil Régional du Centre-Val de Loire

DRAAF Centre-Val de Loire

Lycée agricole de Chartres – La Saussaye

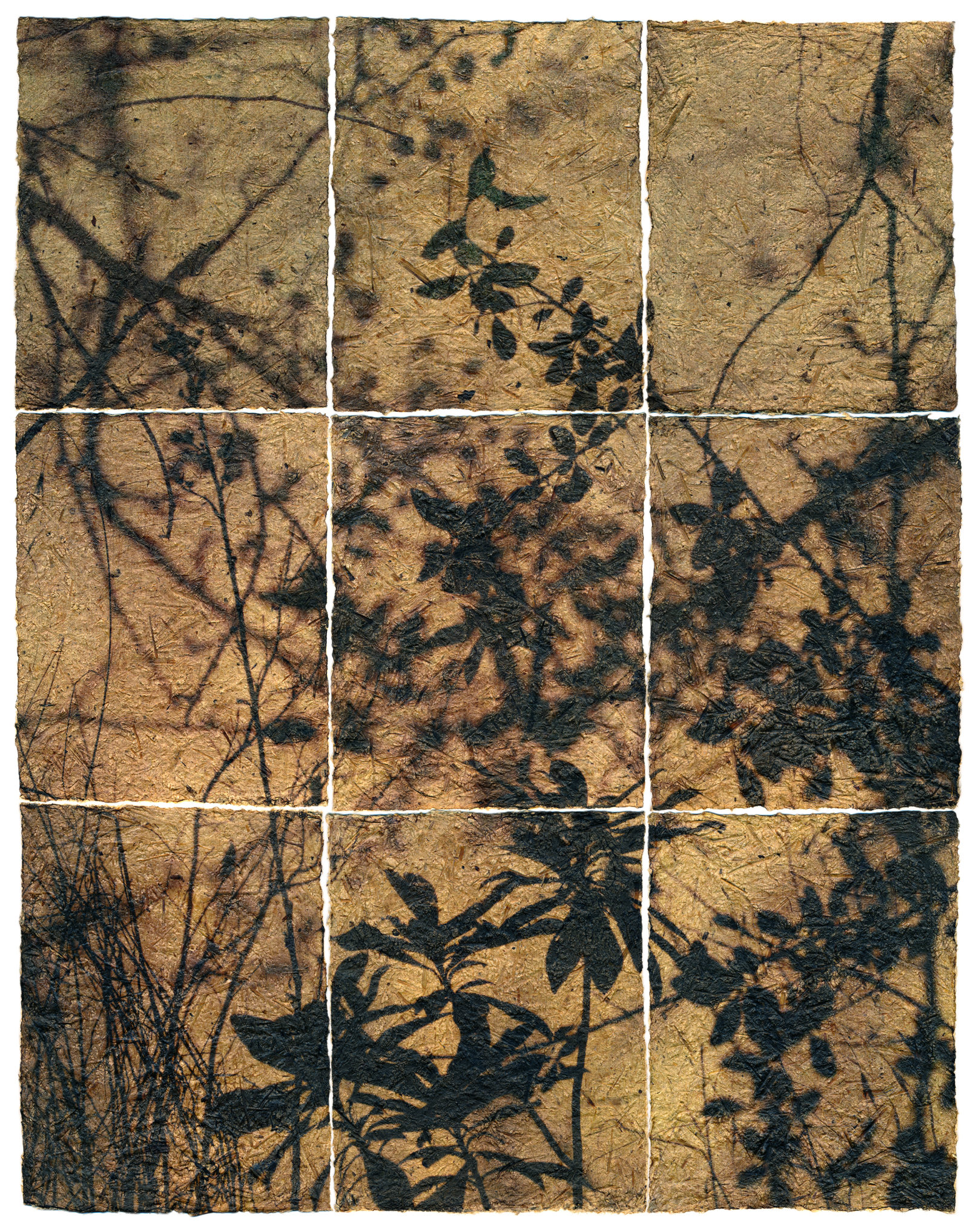

1. Fossil (a reflection on the link between medium and image)

In Europe, paper was mainly produced using an old cloth (cotton), while in Japan, paper was mainly produced using the stems of plants such as mulberry and mitsumata (oriental paperbush). For this reason, papermaking is deeply linked to nature and the texture of paper varies greatly depending on the growing environment of each plant. In recent years, the destruction of nature has greatly affected traditional Japanese paper making. And since it is difficult to find raw materials, this manufacturing is now heavily dependent on imports. The artisans whose work disappears, no longer find the same aspect or quality of the past. The handcrafted paper is a kind of instant image of the environment at a given time. If plants manifest their environment around the school, how can I capture their whispers? Even Nature, which renews itself every year, evolves little by little every day. How can I express this subtle change? Is it possible to return the image to Nature?

Starting from the initial idea of creating Japanese paper using plants from around the school, the project began with the search for plants suitable for papermaking. However, instead of making a perfect paper, I dared to leave a rough texture by using seeds and stems, which are considered impurities in the making of Japanese paper (washi), in order to observe the details of the plants used.

Initially, the idea was to take pictures of parts of the forest with a view camera (4 x 5 inch), use the plants in the pictures to make Japanese paper, and then print the images taken with the view camera on the handmade paper. However, after many visits to the forest and observing the shadows of the plants cast by the sunlight on the ground and trees, I found inspiration in W.H.F. Talbot's "photogenic drawing". The paper, the plant on which it is placed (positive) and the shadow of the plant fixed by the sunlight (negative)... The relationship between negative and positive, so banal for the generation familiar with film photography, will have a completely different meaning for the digital generation, which deals exclusively with positive images. It is perhaps useful to look at the relationship between the medium and the photographic image in this era of digitalization?

With these ideas in mind, in Fossil, I wanted to talk about the relationship between the negative and the positive, the photographic image and the medium, by photographing the shadows of plants projected onto a white drape brought to two different forests, the bois parisien and the six muids, making paper from the photographed plants and printing the photographs of the shadows onto the fabricated paper. To fix the shadows of the plants on the paper, I imagined an image transfer technique using tattoo stickers, inspired by the idea of photographic fixation before the birth of photography, as described in the "Giphantie" written by Charles-Francois Tiphaigne de La Roche in 1760:

"...You know that the rays of light, reflected from different substances, take a picture and paint these substances on all polished surfaces, on the retina of the eye for example, on water, on ice. The elemental spirits have attempted to fix these transient images; they have composed a very subtle, very viscous material, very quick to dry out and harden, by means of which a picture is made in the twinkling of an eye. They apply this material to a piece of canvas and present it to the objects they want to paint. The first effect of the canvas is that of a mirror; we see all the surroundings and distant bodies in it, whose image the light can bring. But what a mirror cannot do, the canvas, by means of its viscous coating, retains the simulacra. The mirror renders the objects faithfully but keeps none of them; our canvases render them no less faithfully and keep them all. This impression of the images is the tricky thing at the first moment when the canvas receives them: you take it off at once, you place it in a dark place; an hour later, the coating is dried up, and you have a painting even more precious, that no art can imitate the truth of it; and that time can in no way damage it... "

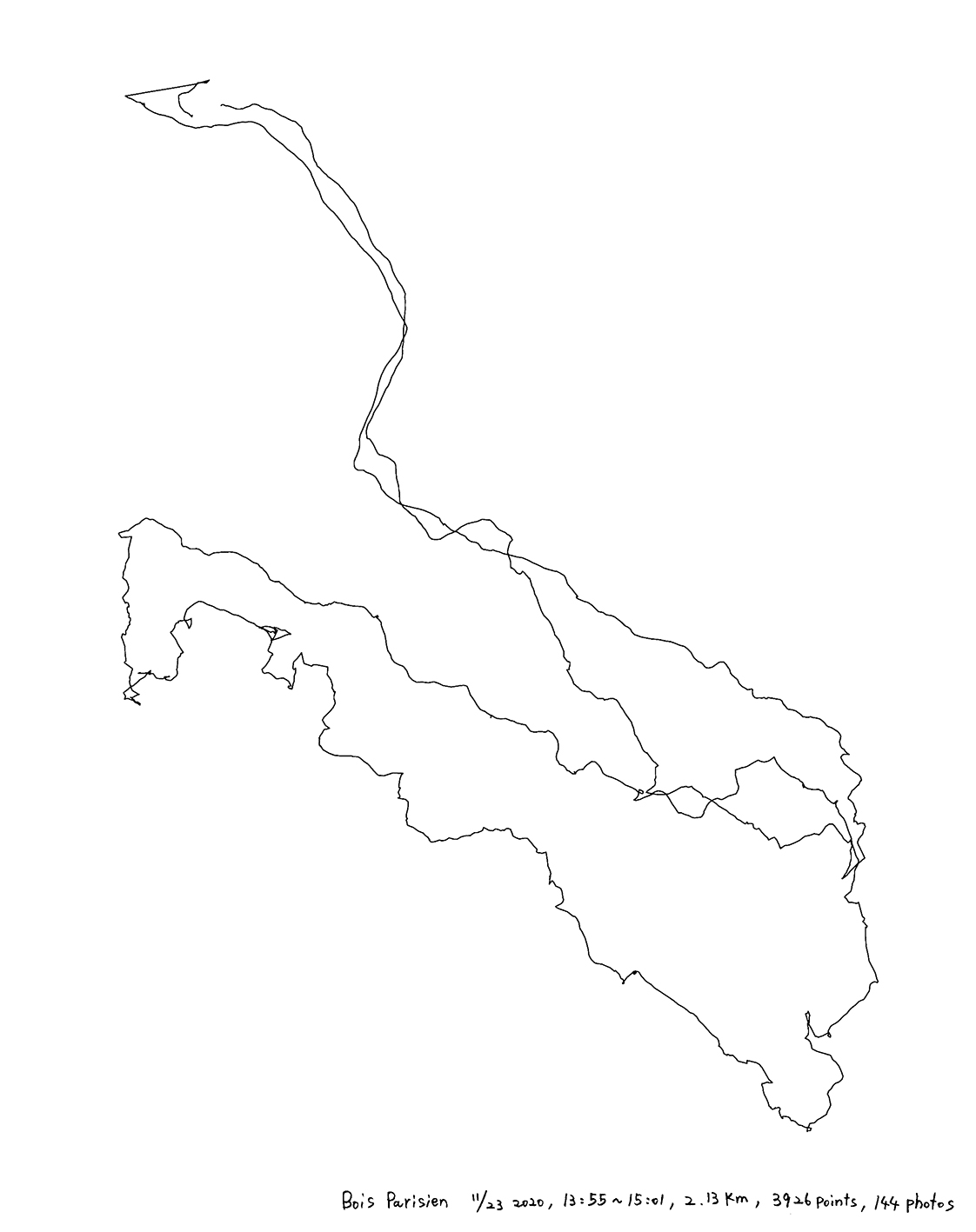

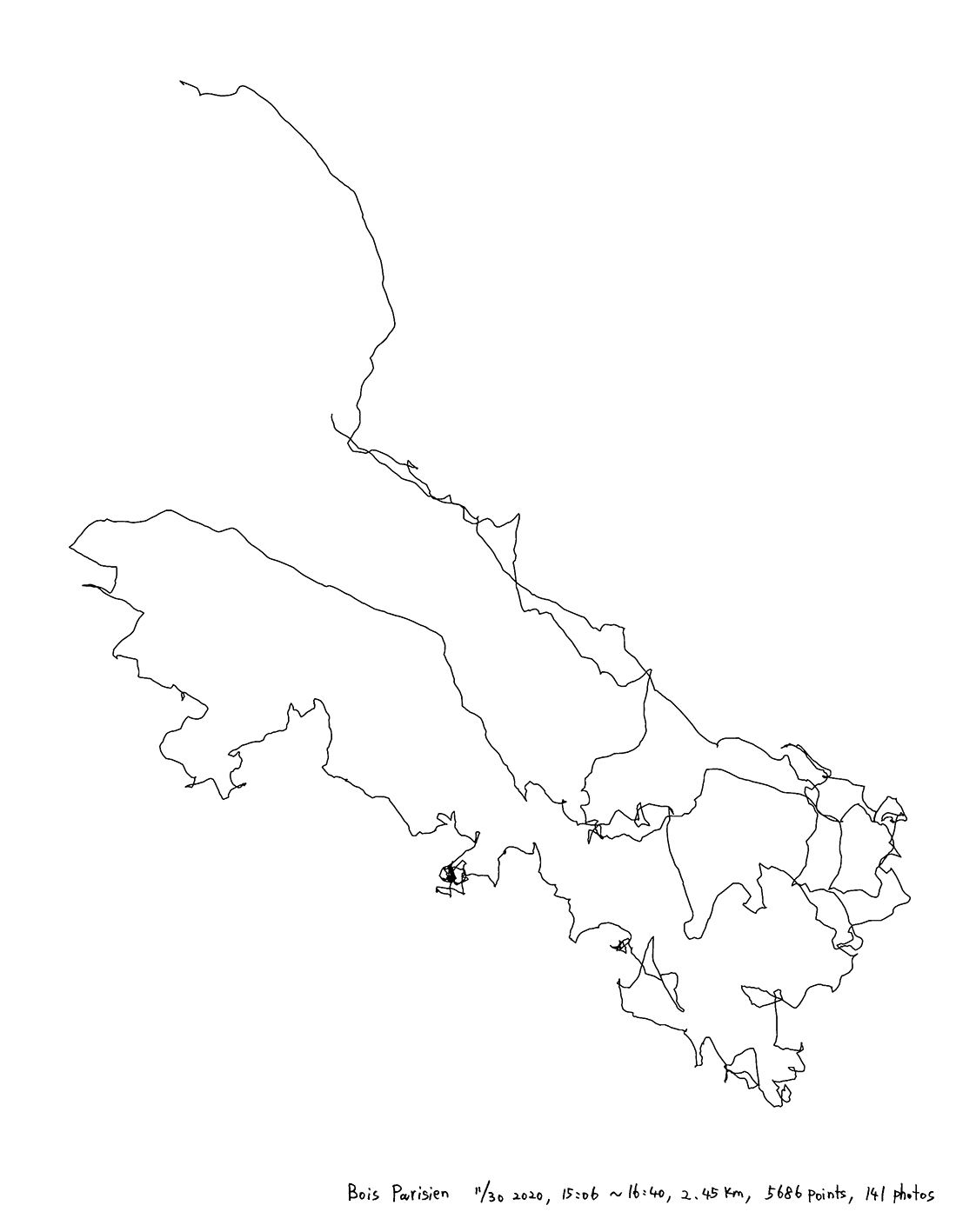

2. Trails (a reflection on light and color)

Trails was born during the creation of Fossil, inspired by Claude Monet's "Cathédrales de Rouen" series.

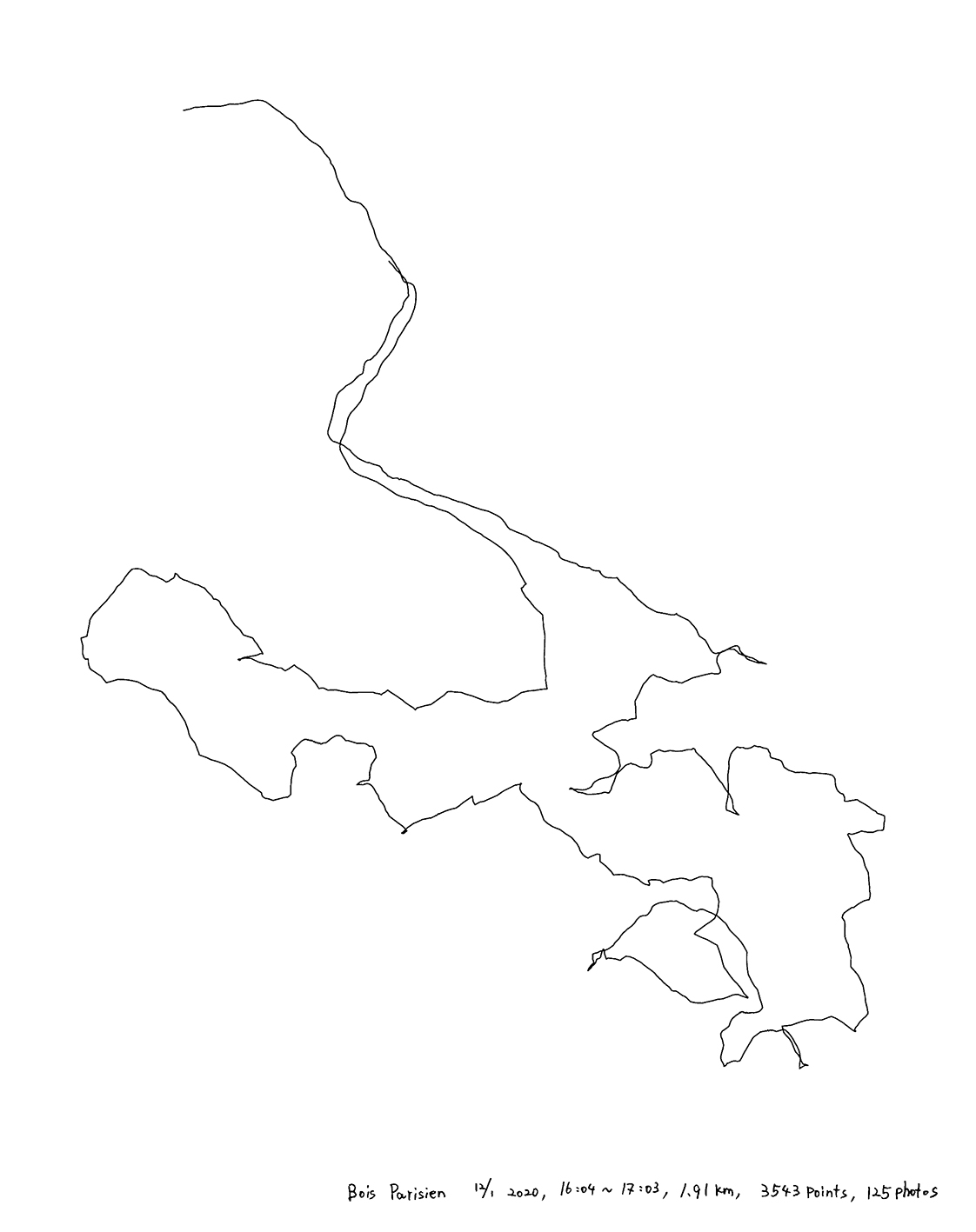

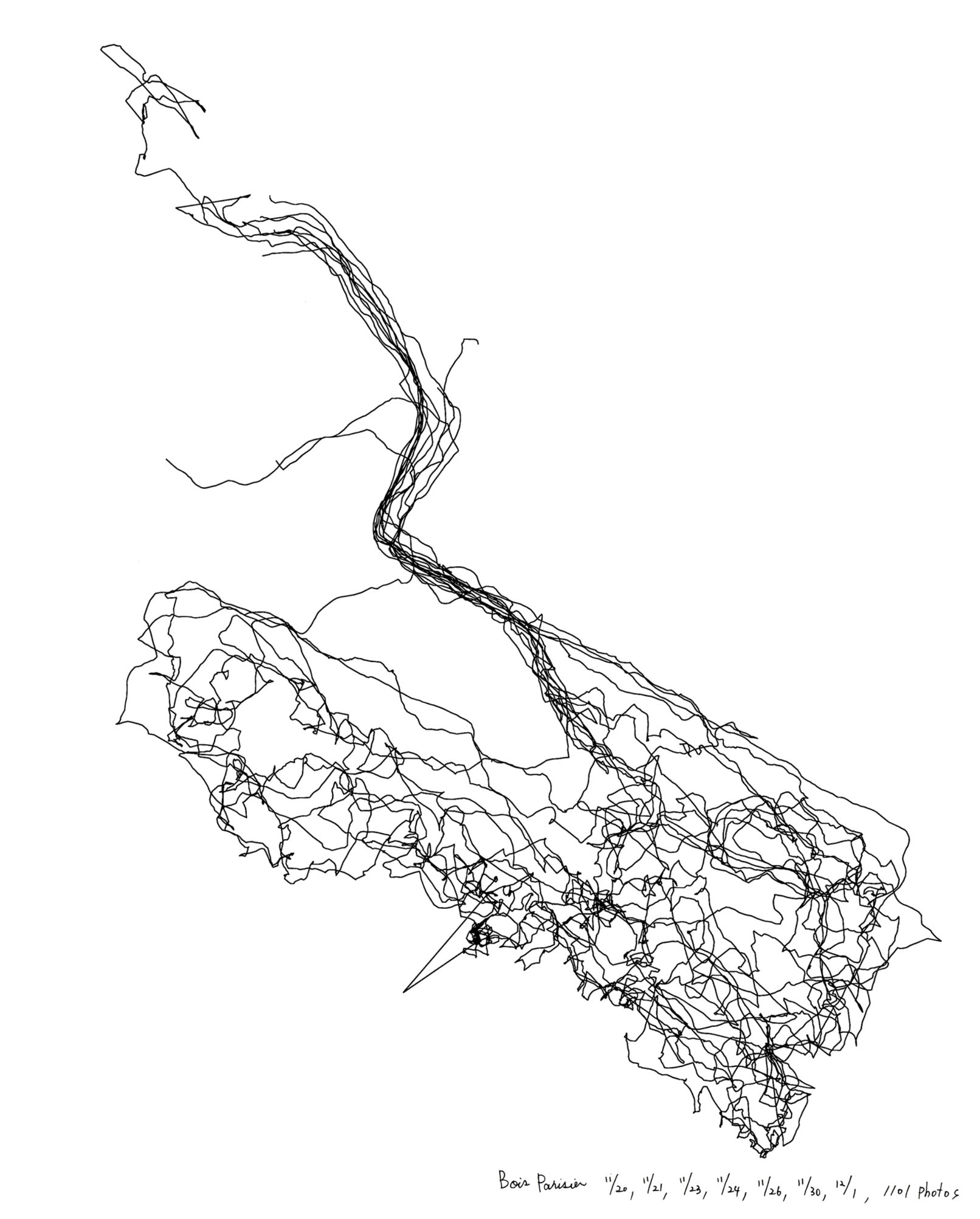

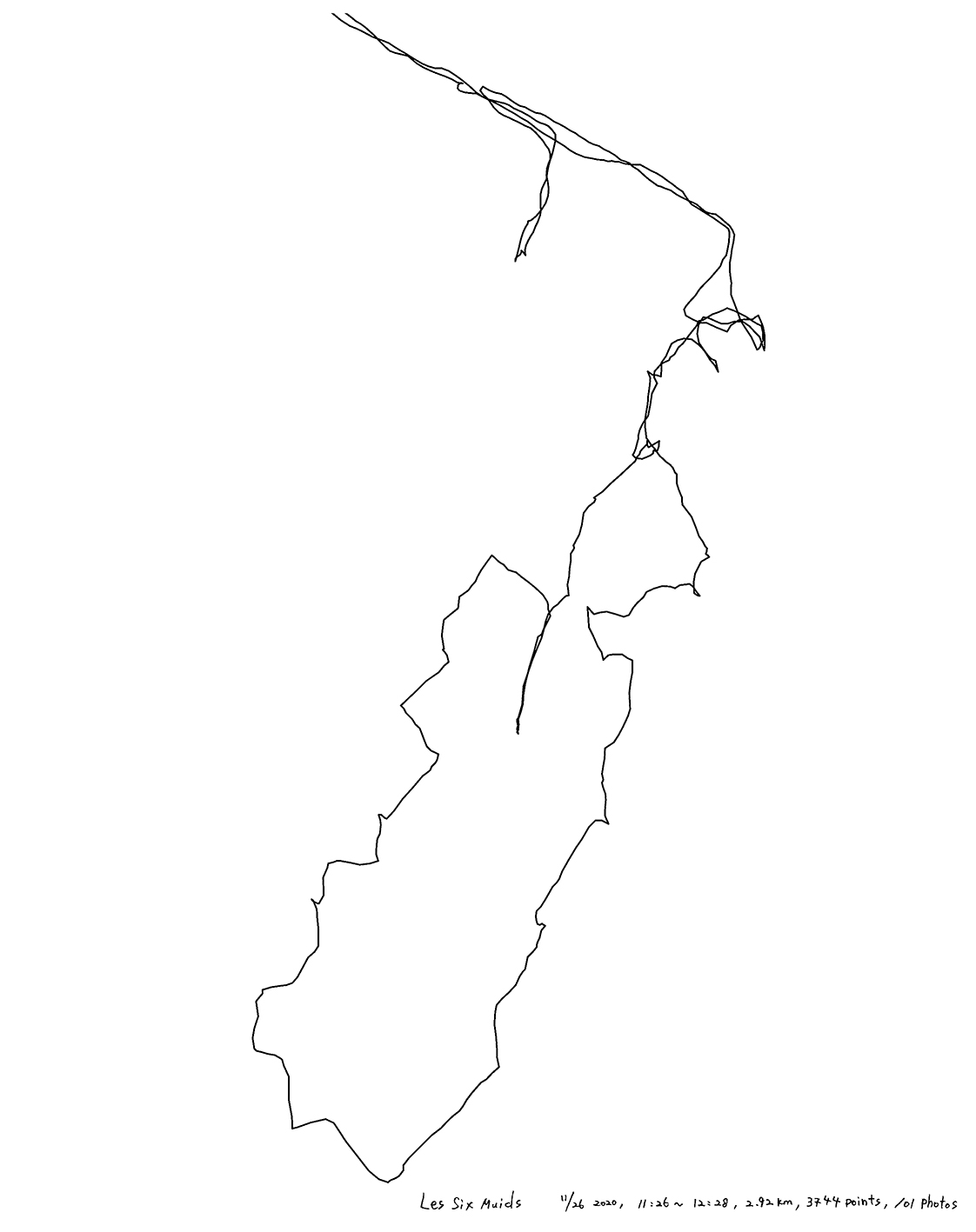

At the beginning of the Fossil project, I visited every day two forests, Bois parisien and the Six muids, to look for the most representative place for me, but I could not choose them, because every day, while walking in the woods, I realized that it is the light and the colors that symbolize these woods. Rather than choosing one place, perhaps it is the physical movement of wandering through the woods that represents them to me...

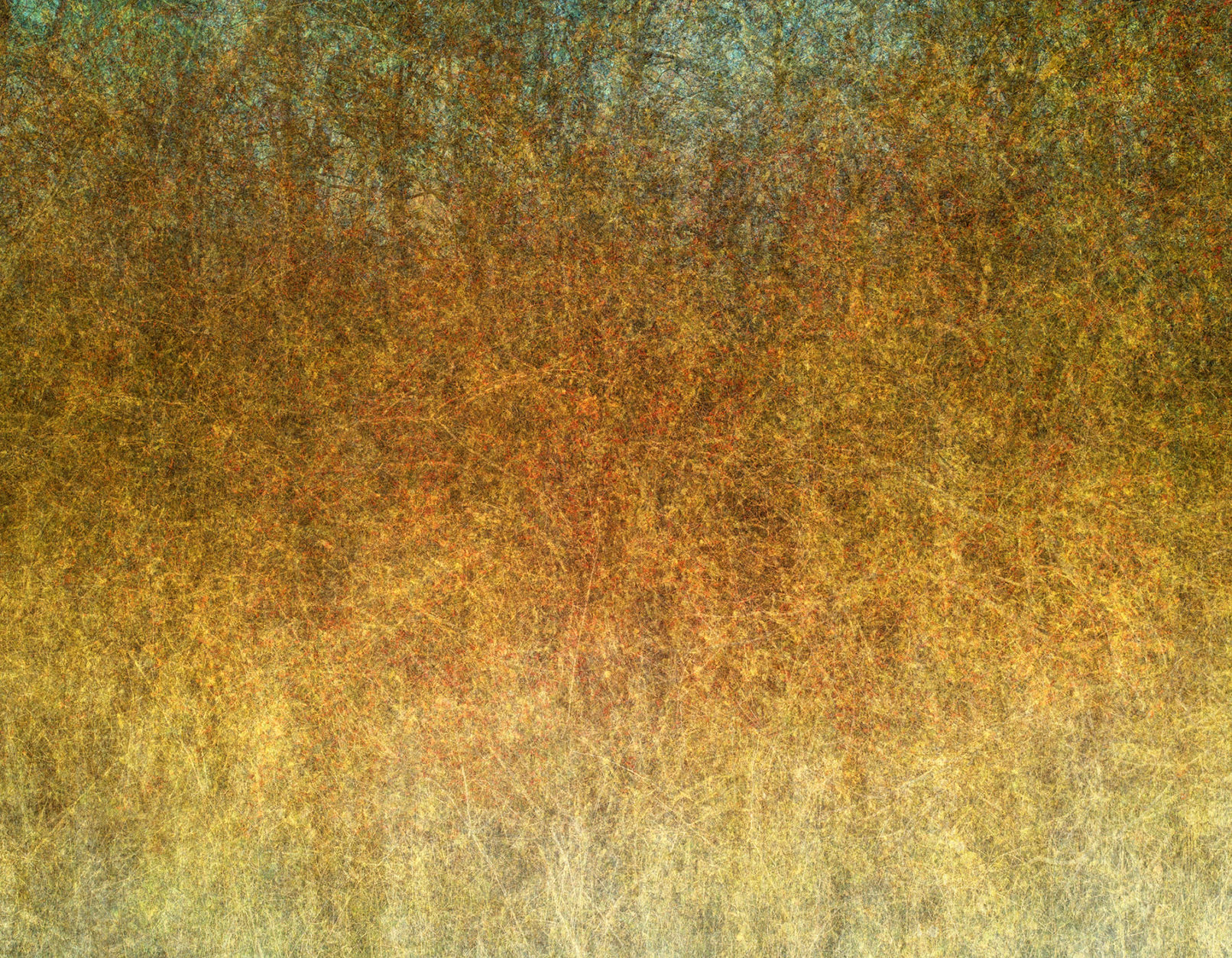

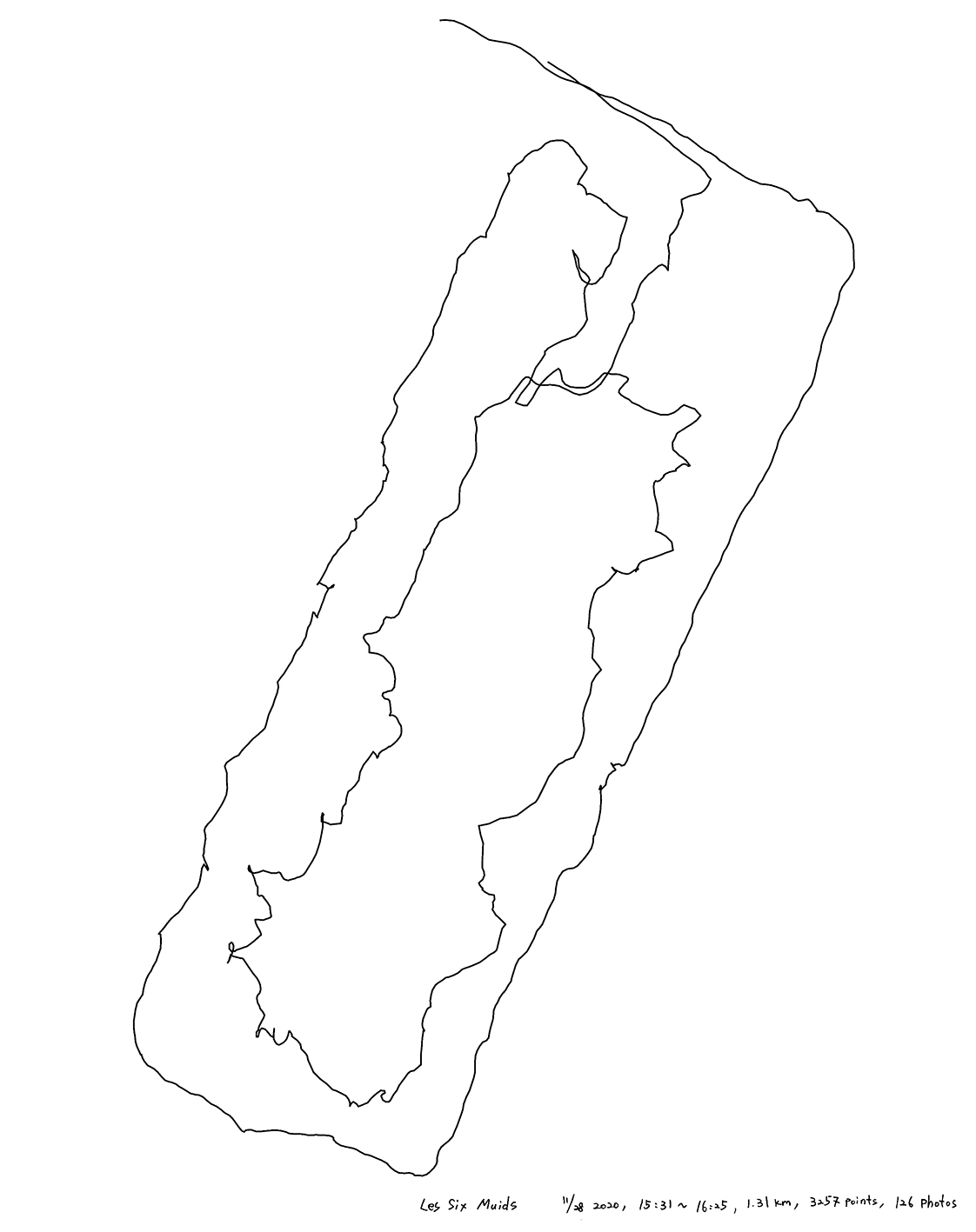

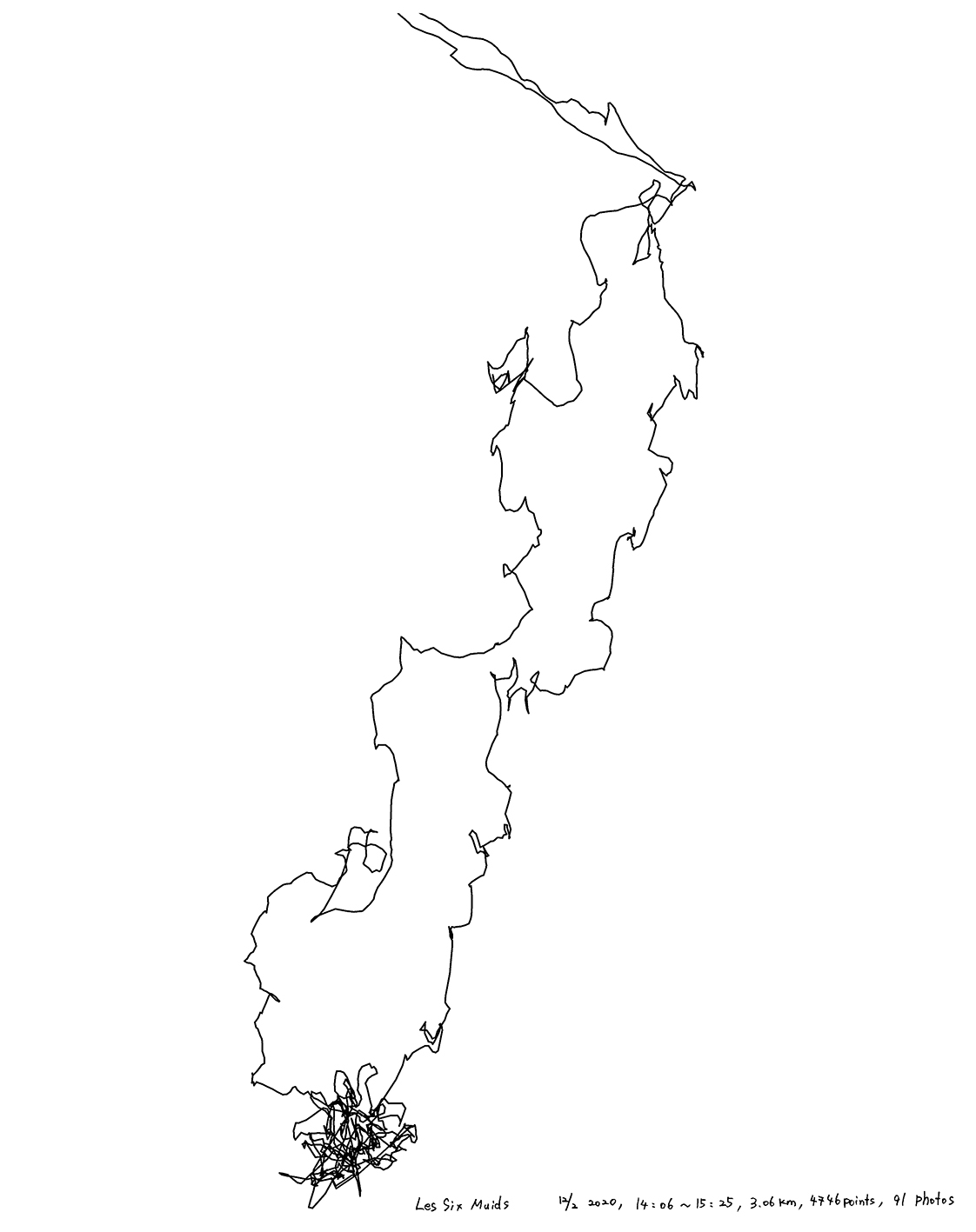

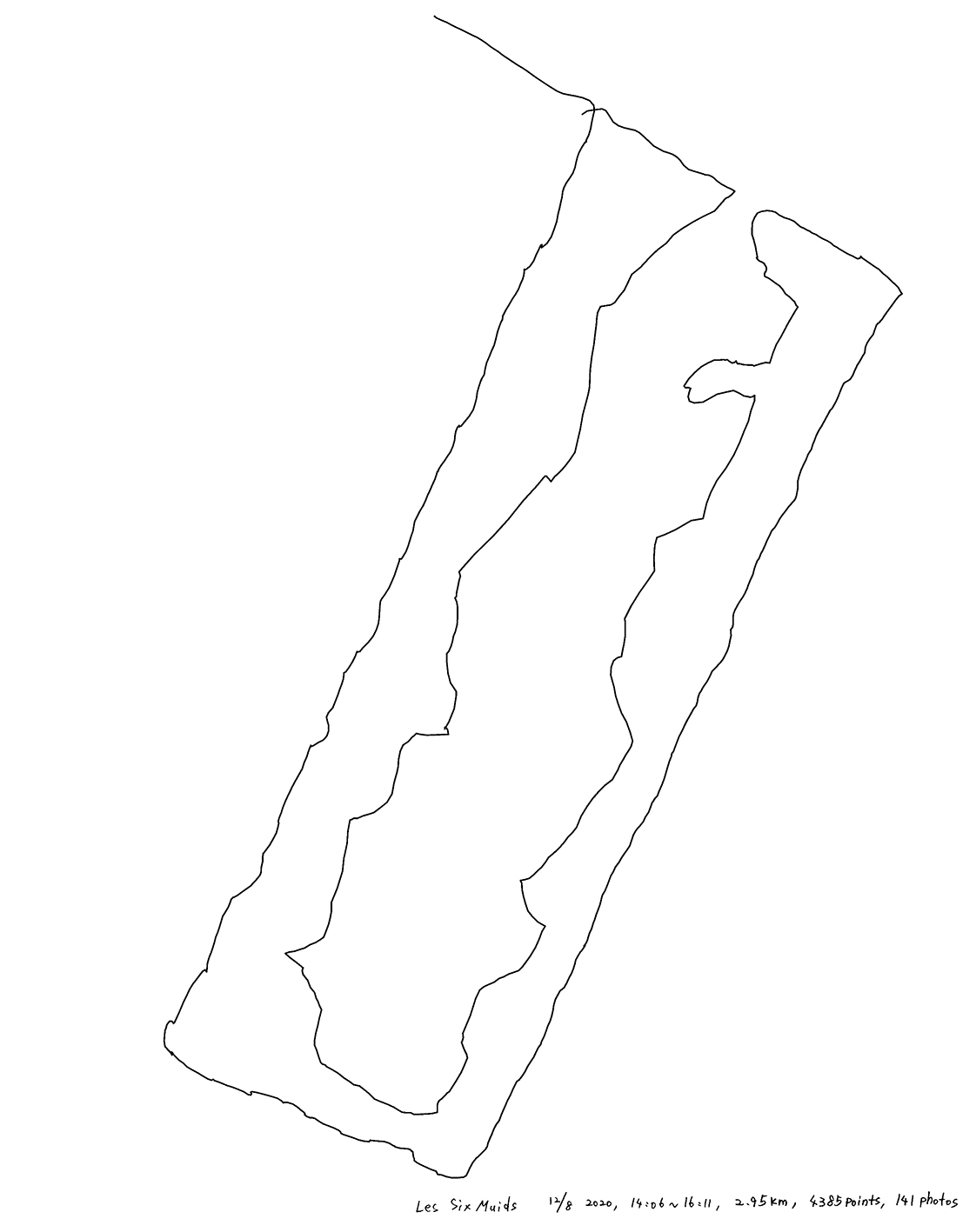

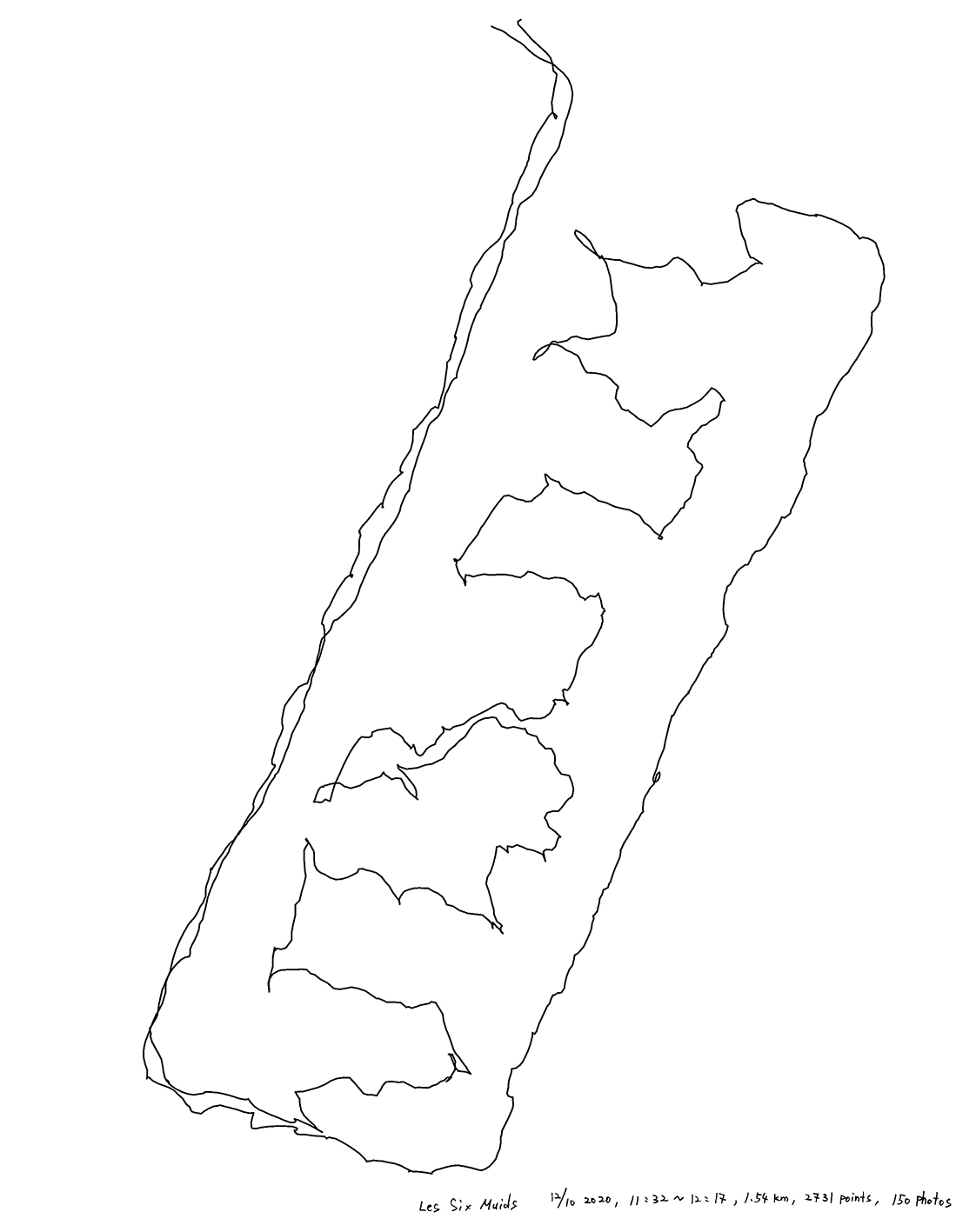

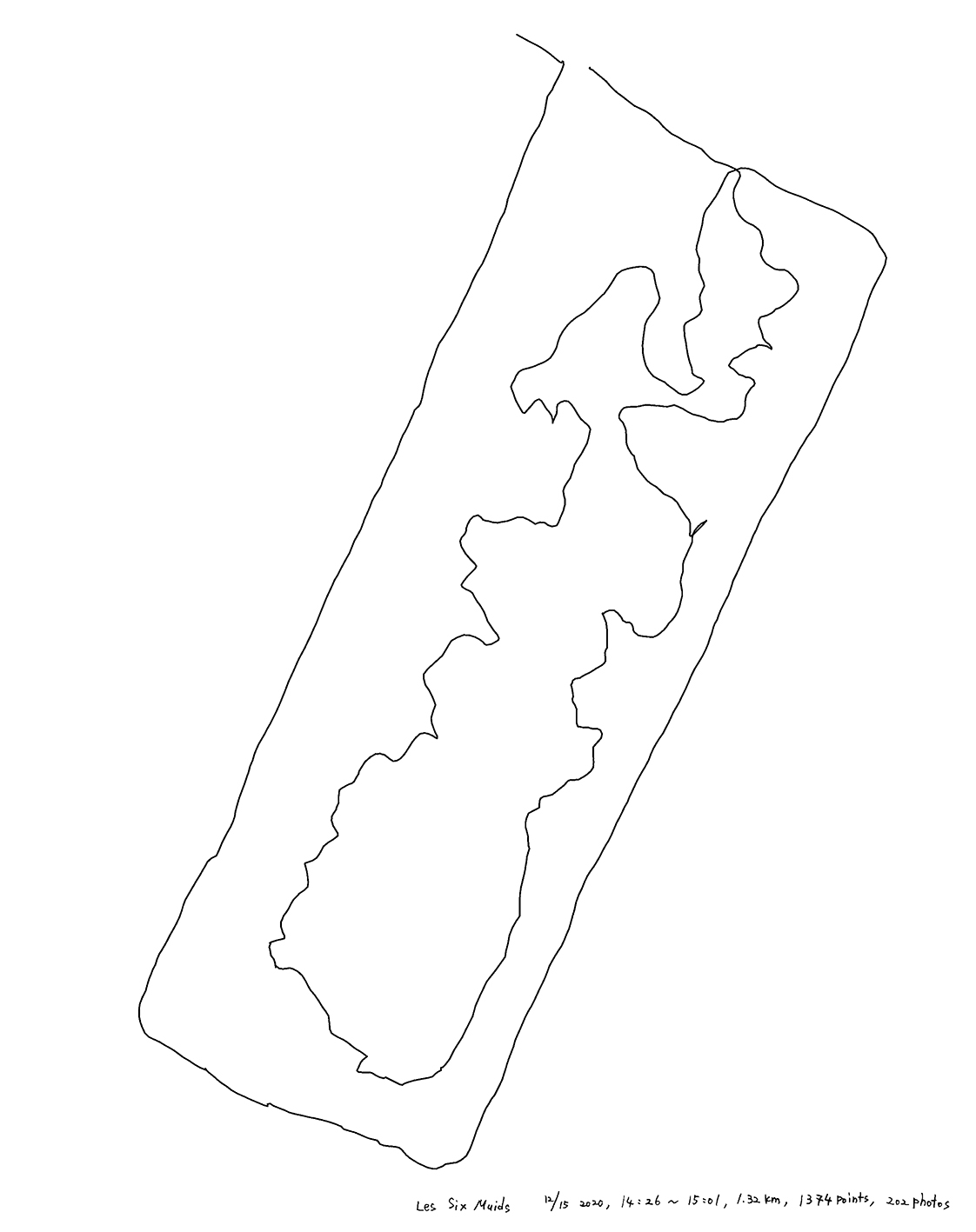

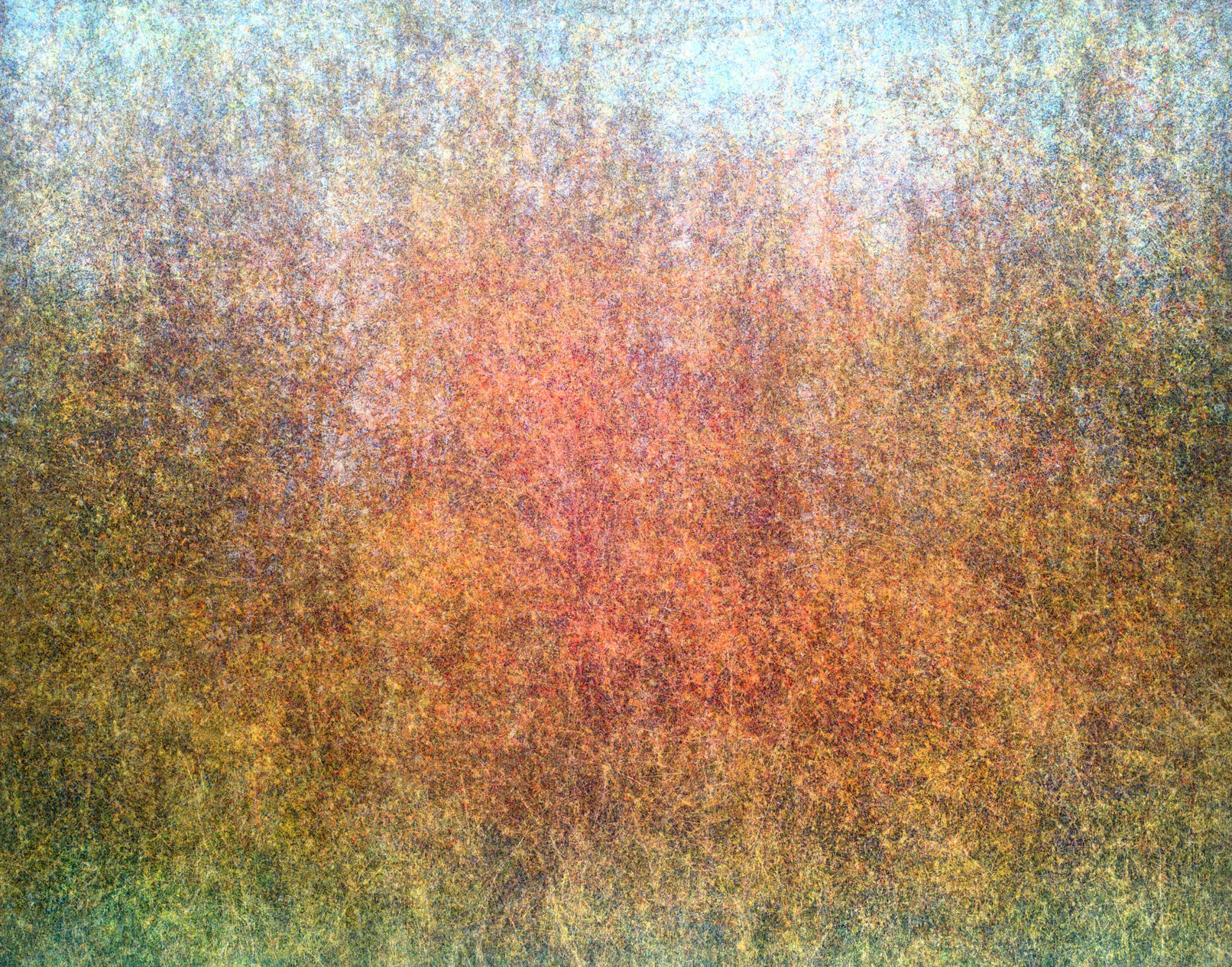

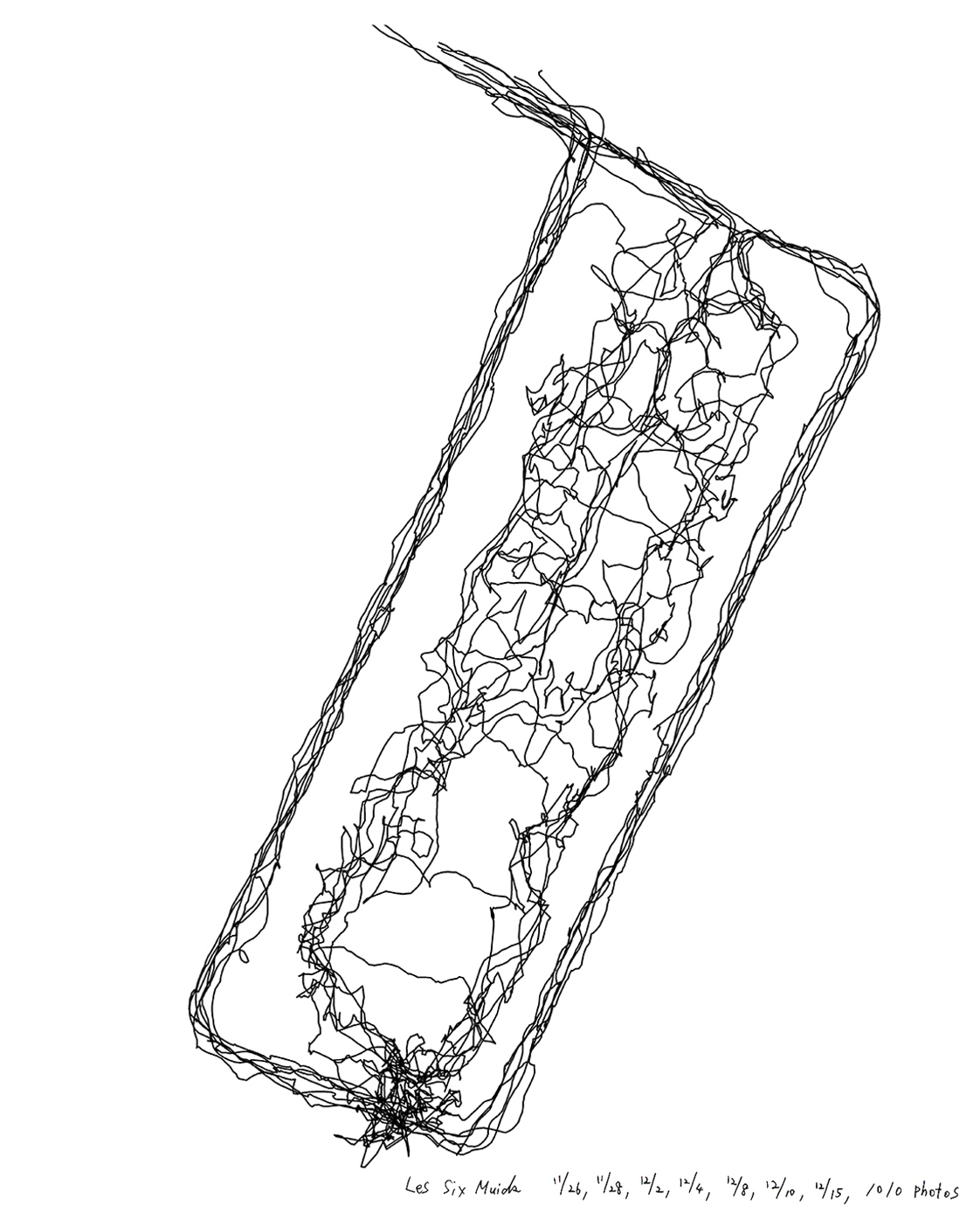

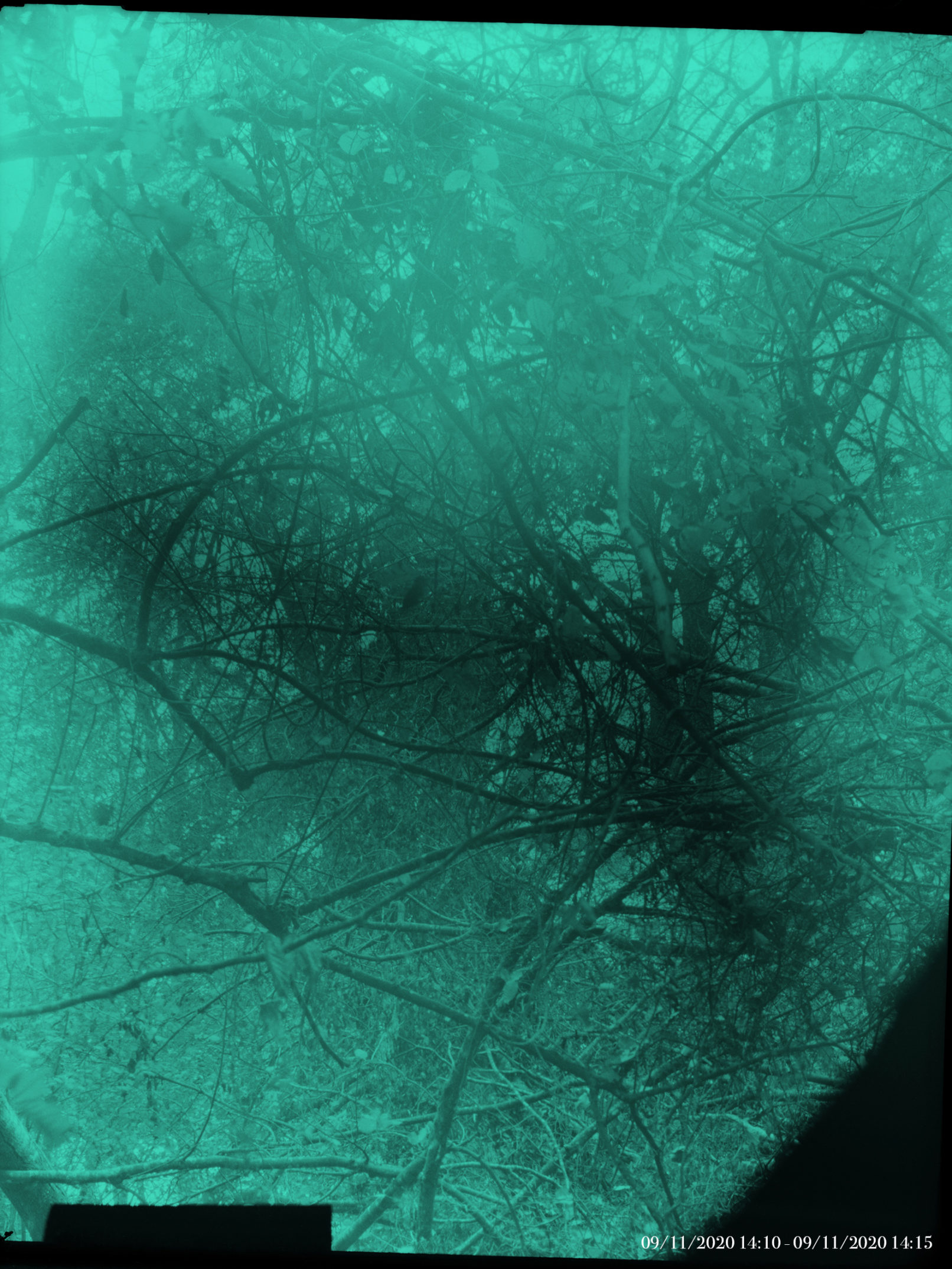

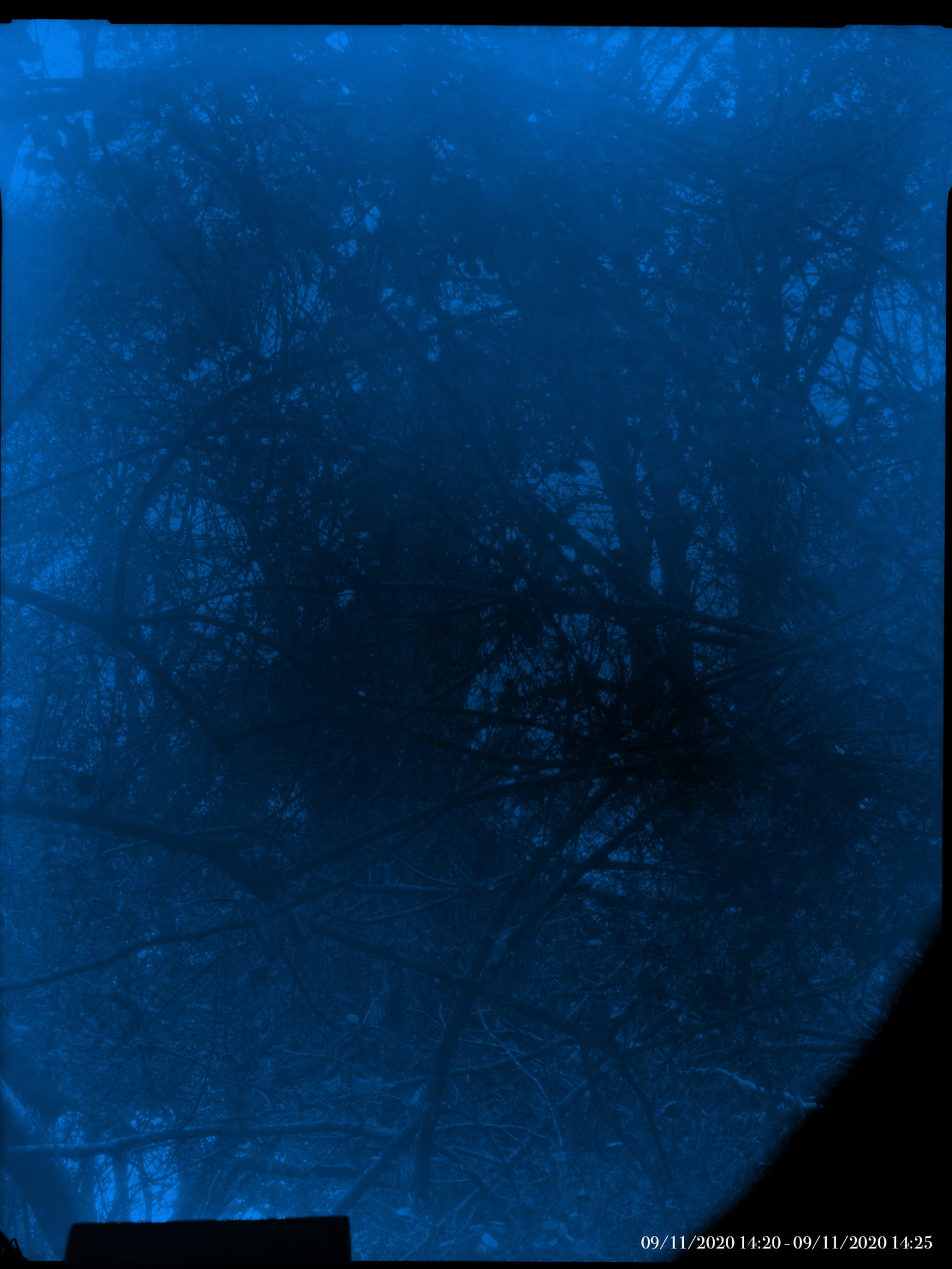

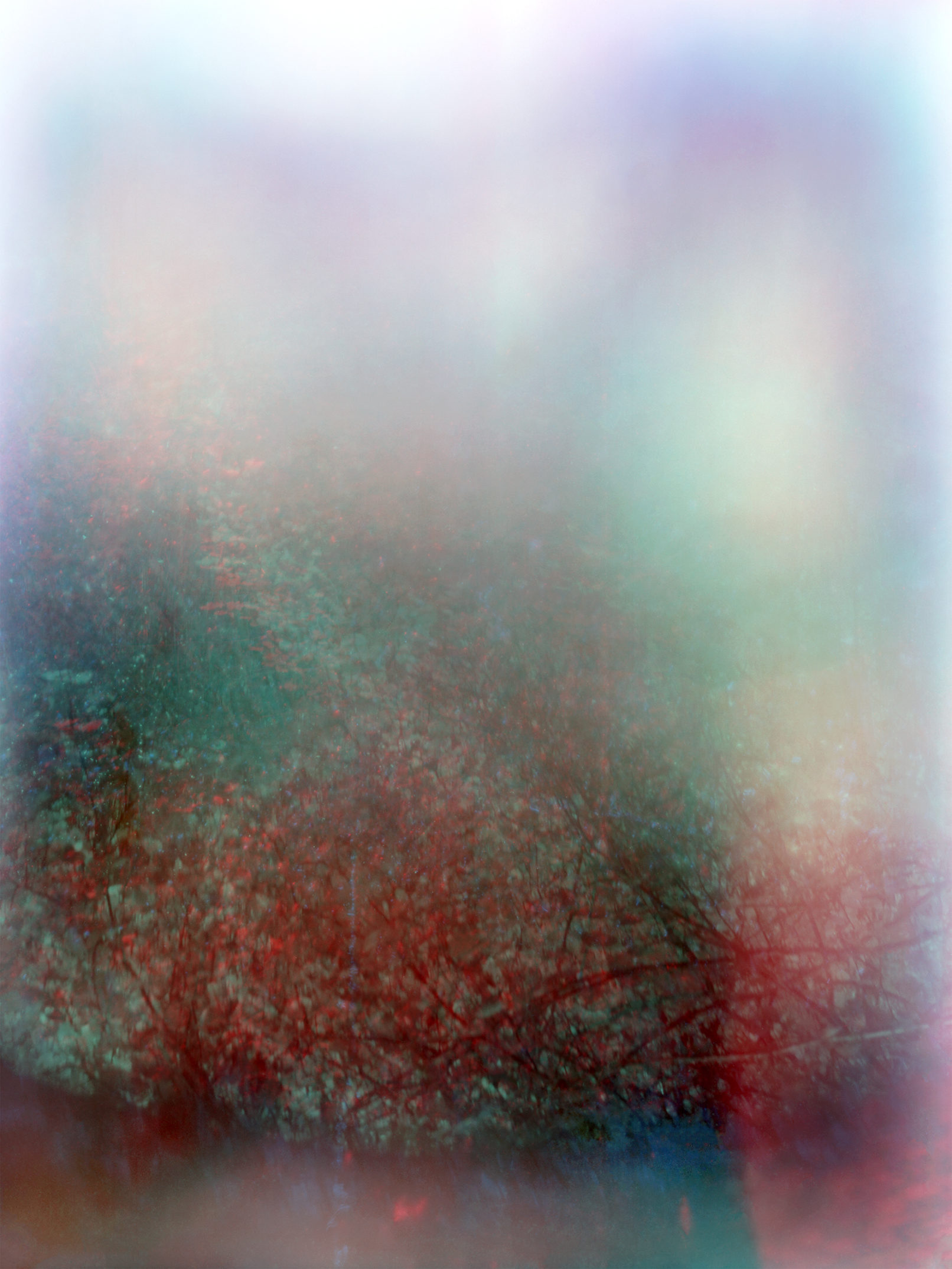

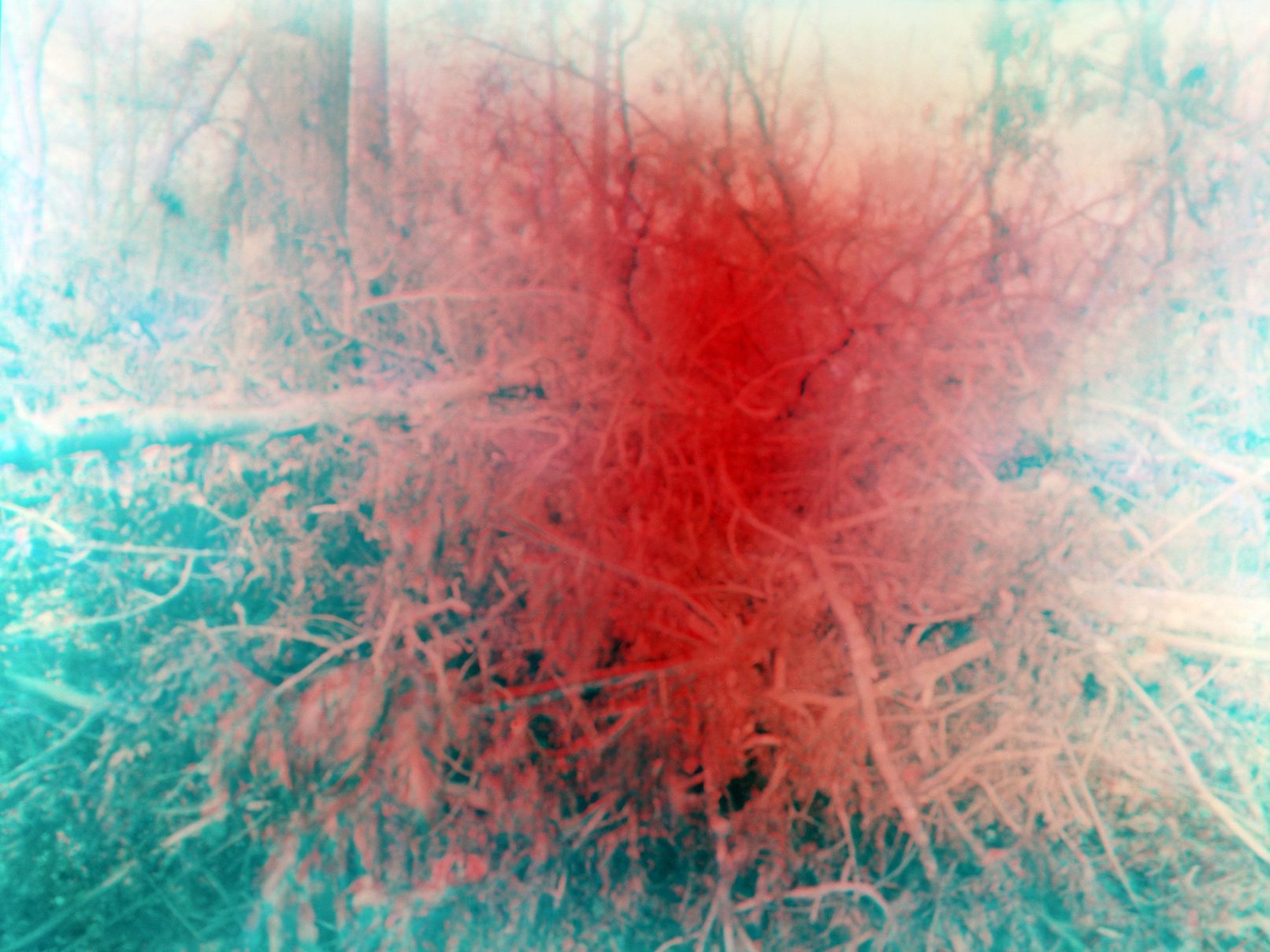

For this reason, just as C. Monet repeatedly painted the Rouen Cathedral on different days, at different times, and in different light, I decided to preserve the appearance of the Bois parisien and the Six muids by taking hundreds of photographs on different days, in different weather conditions, and at different times, and overlaying them on a computer. At the same time, in order to visualize how I traversed the forest in different ways each day, I used GPS software to record the route. Finally, by overlaying all the photos and GPS readings from the seven days, I was able to establish the light, colors, and path of each of the seven days of the forests.

The image of the forest, created by overlaying a thousand photographs, has lost the details that would have allowed me to identify the location, and all that remains in the end is the light, color, and tracks. It is as if I were painting a forest in my memory, where only the sound of falling leaves, the light and the colors remain clear...

3. RGB (a reflection on color and time)

In " Le boulevard du Temple ", photographed by L. Daguerre in 1838, the shooting time of 15 minutes is recorded. During this shooting time, everything that moves disappears from the image, and only what is still for 15 minutes is fixed in the image, eternally. I have always been fascinated by these traces of time that can be found in a photograph. It seems to me that this is exactly the "natural magic" that W.H.F. Talbot talks about...

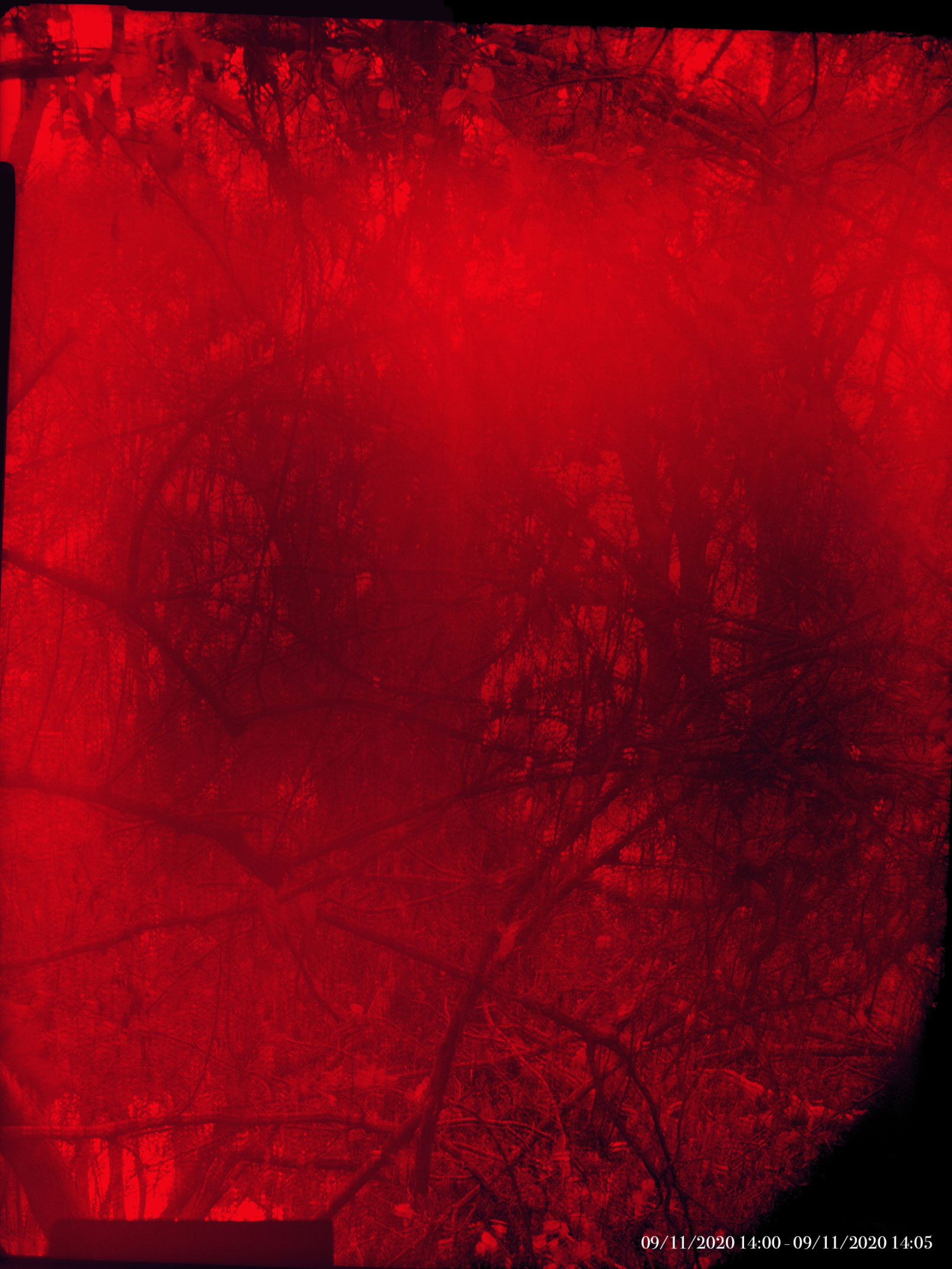

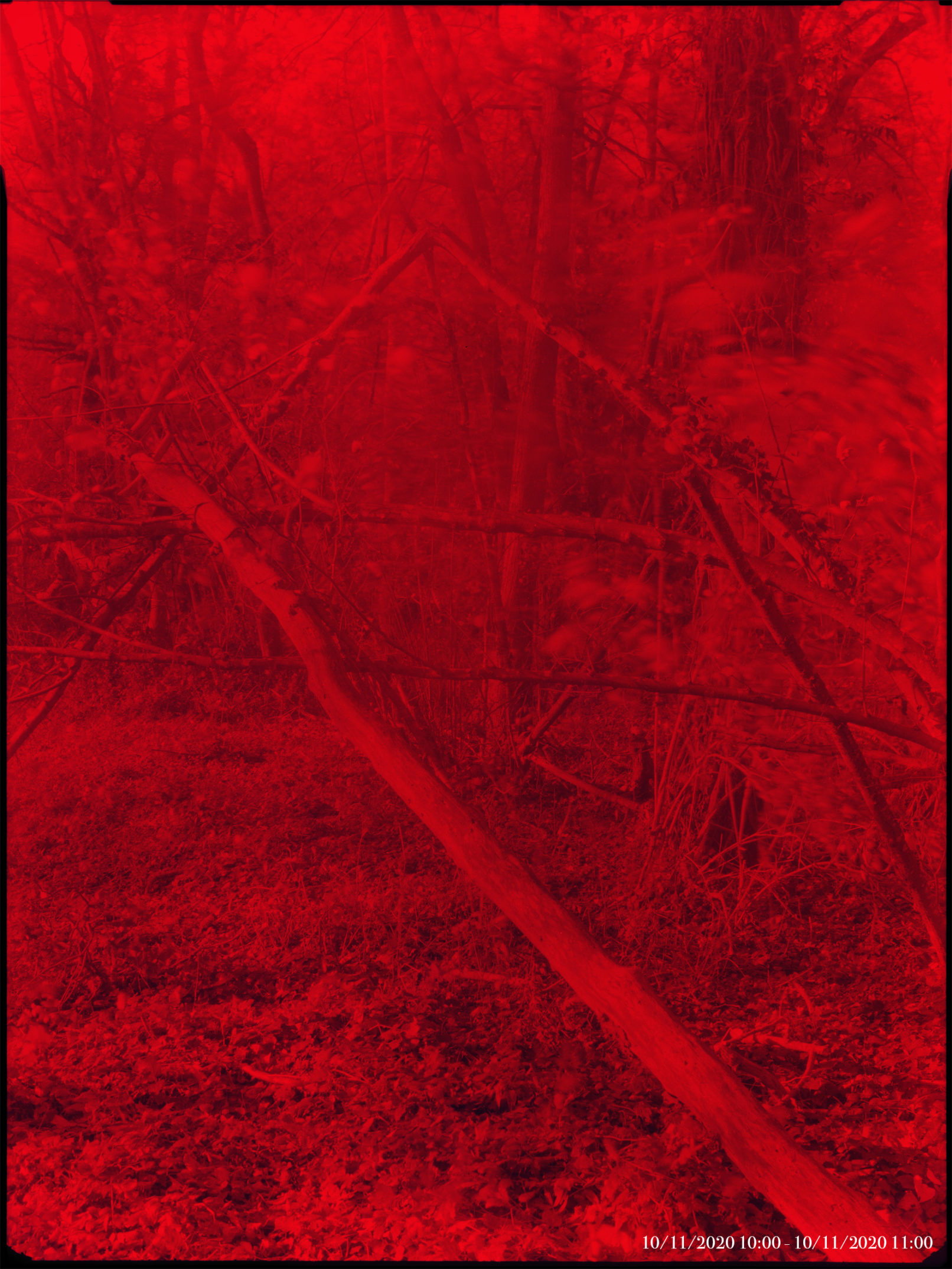

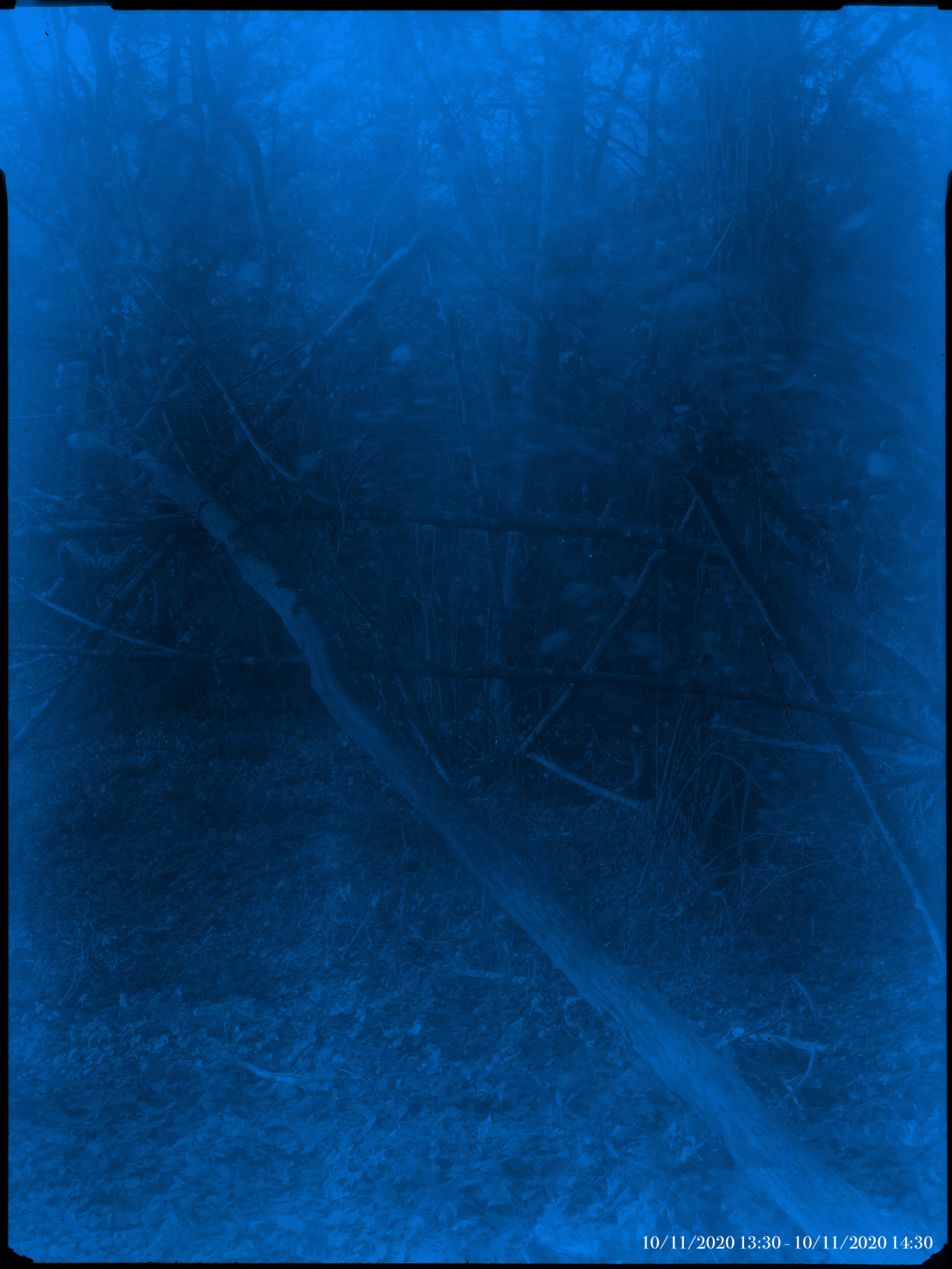

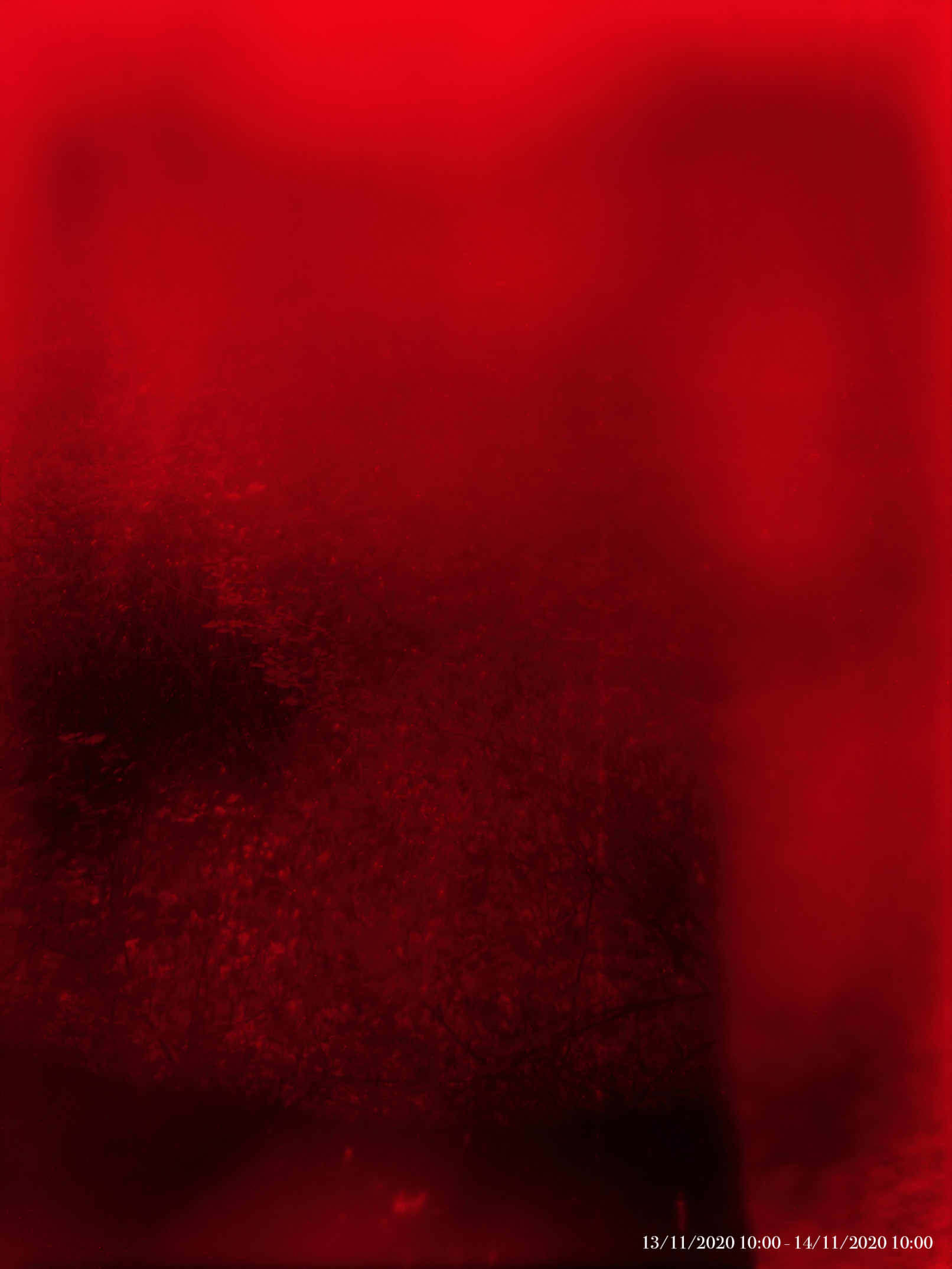

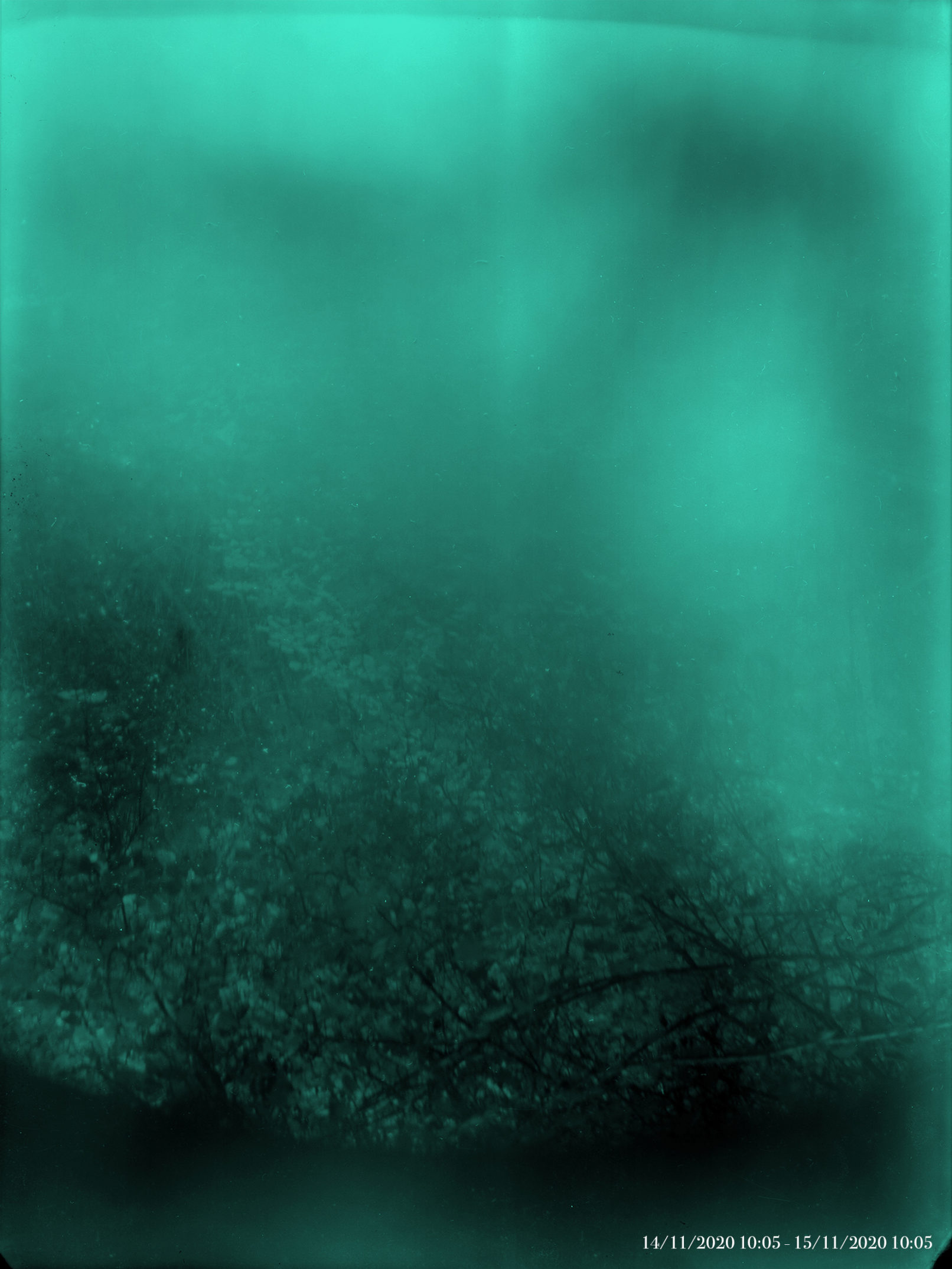

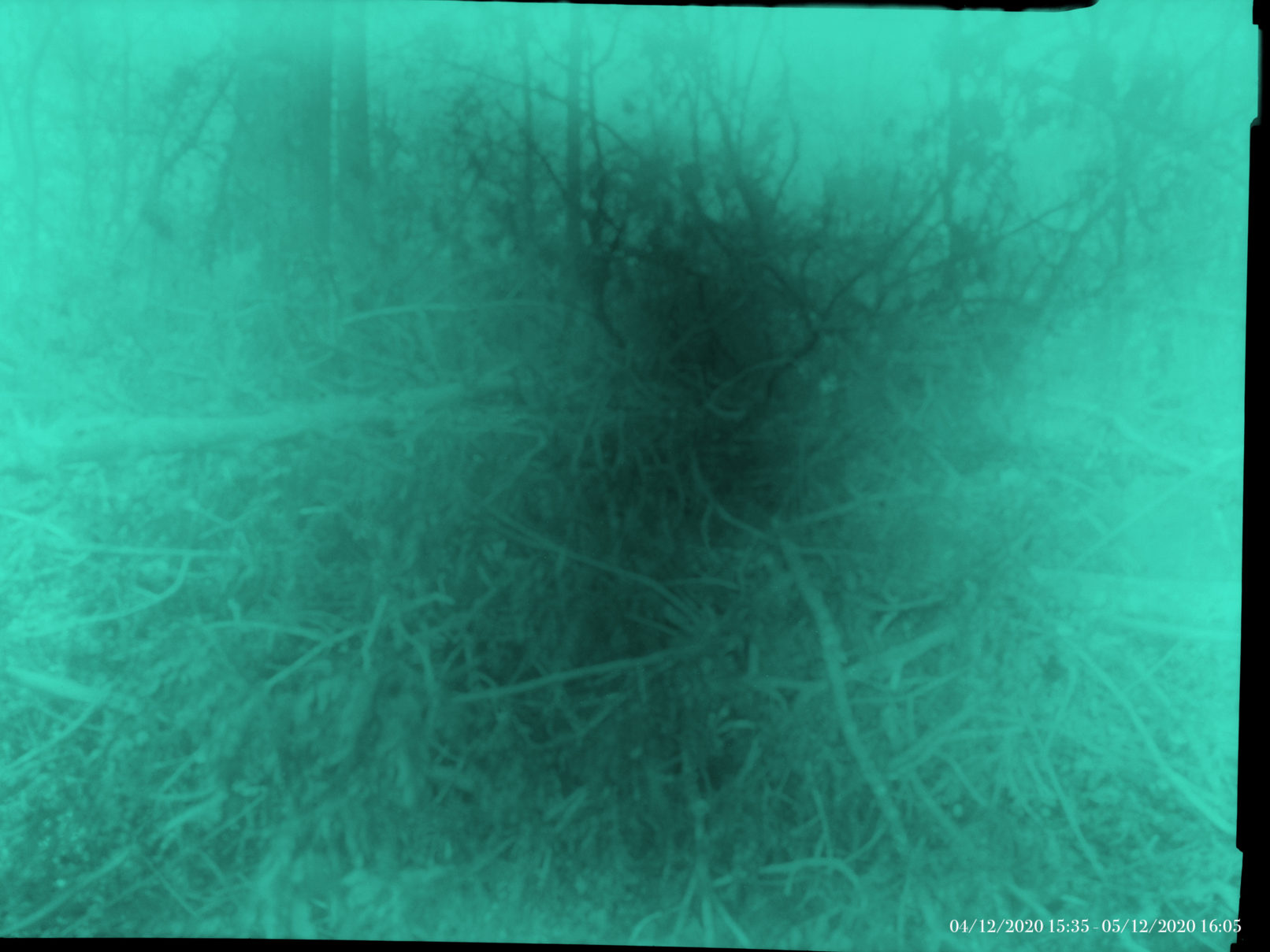

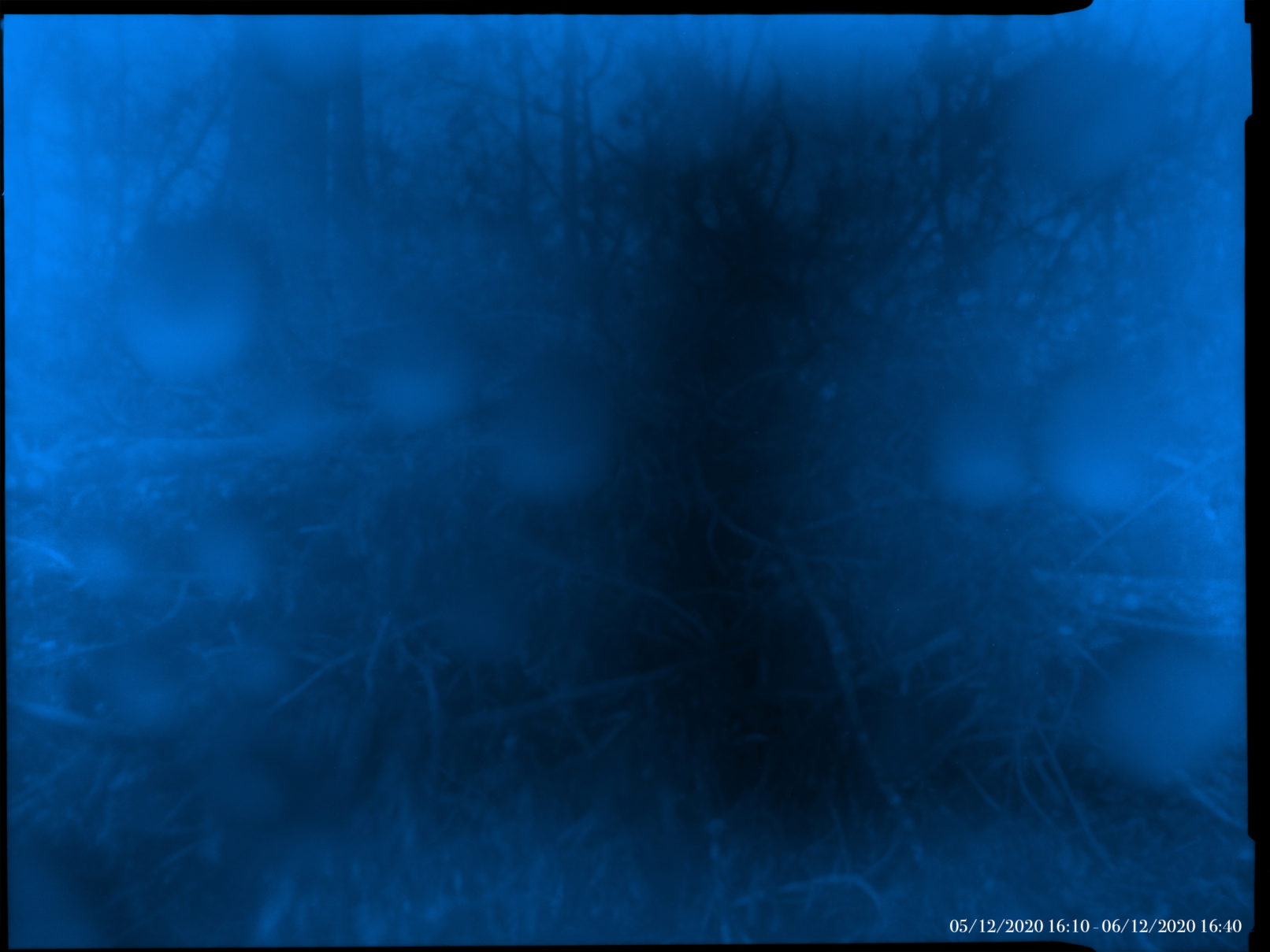

RGB was created at the same time as Trails. While Trails was about light and color, RGB focuses on using color to visualize time. This project was inspired by the world's first color image, obtained by James Clerk Maxwell in 1861 in England. J.C. Maxwell was able to record color information on a black and white photographic plate by attaching filters of the three primary colors - red, green and blue - to the front of the lens. He then used three projectors, each equipped with the exact same filters used to take the photographs, to project the photographs onto each other, producing the first color image. The color imaging method he developed was widely used in Hollywood between 1922 and 1952 to produce color films (Technicolor) and is still used today for the basic colors for LCD screens.

RGB is not only a tribute to the method of color imaging he suggested, but also an experiment to see how time can be visualized through the use of color. For this reason, I photographed in black and white film with red, green, and blue filters in front of the lens, as Maxwell suggests, but I left my pinhole camera open for 24 hours. As a result, even though the photo was taken from a fixed point, the movement of trees in the wind, or the movement of animals at night, create areas of color that either overlap or do not overlap in the photo. The overlapping areas produce a color image, while the non-overlapping areas show the primary colors red, green and blue. In other words, in the areas where the primary colors are visible, we can see the "time" the image was taken.